What Are Our Foundations?

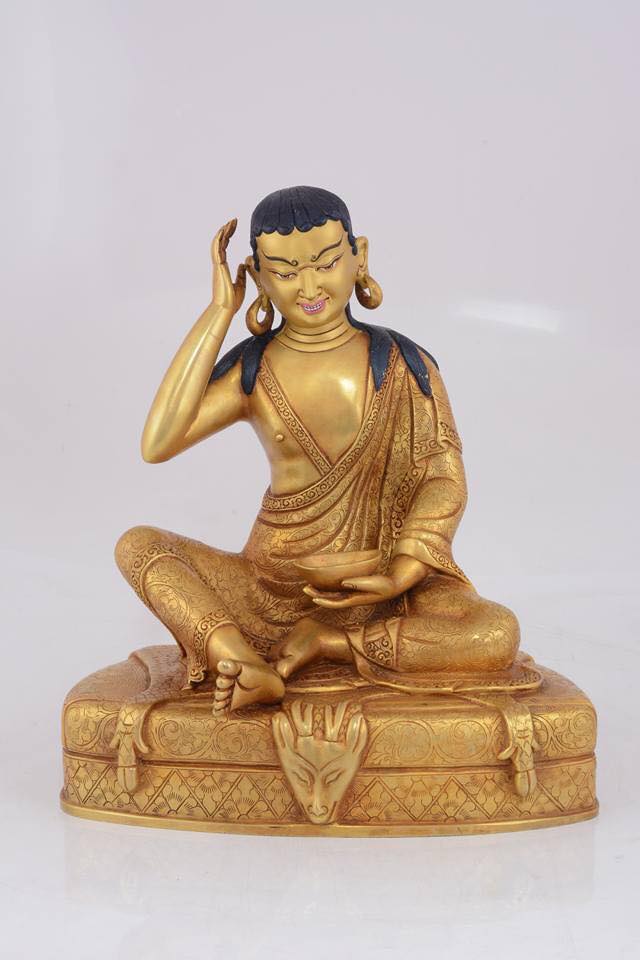

Serlingpa’s Advice To Atisha

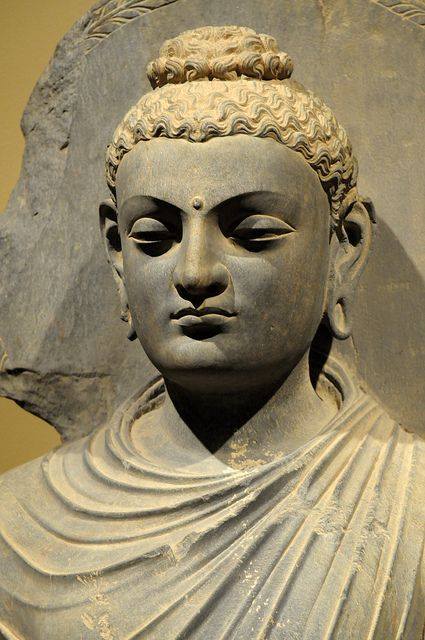

Form and Selflessness

What is meditation?

Bordo Dialogue 2021

Living the dharma – How to foster Bodhicitta in community life

Part 1

June 27th 2021

Part 2

August 8th 2021

Transforming Suffering and Happiness into Enlightenment.

Whenever we are harmed by sentient beings or anything else, if we make a habit out of perceiving only the suffering, then when even the smallest problem comes up, it will cause enormous anguish in our mind.This is because the nature of any perception or idea, be it happiness or sorrow, is to grow stronger and stronger the more we become accustomed to it. So as the strength of this pattern gradually builds up, before long we’ll find that just about everything we perceive becomes a cause for actually attracting unhappiness towards us, and happiness will never get a chance.

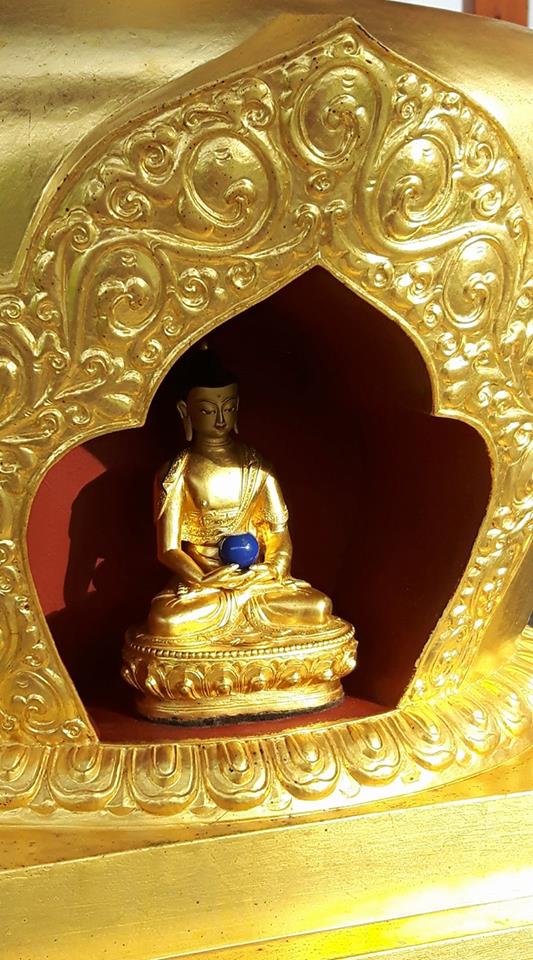

Amitabha and the Pure Land of Sukhavati

Pure Land of Sukhavati

Introduction

Generally, it can be said that there are many pure lands, many paradises of Enlightened Beings we call Buddhas. The Pure land of Great Bliss of the Buddha of Boundless Light, Amitabha, is quite a unique place. There are pure lands in the four directions, East, South, West, North, and in the center. Among them, the pure land of Amitabha is the easiest to get to and therefore quite special. By formulating a special aspiration to be reborn in the pure land of Great bliss, one can accomplish the transference of one’s consciousness to that pure land. The power of prayer, the power of devoted and fervent aspiration, is all that is necessary.

It is said that the pure land of Amitabha Buddha, in relation to our universe, is in the western direction and above our universe. For now, we do not have the ability to perceive it or to go there, because we have not accumulated the necessary karma to be born in such a place, even if that realm exists somewhere, in some manner. We imagine it a bit like the moon, but we do not have yet the opportunity to see it or to be born there.

Dewachen is a manifestation of Buddha Amitabha’s activity. This Buddha has completed the ten perfections, and thanks to the merit thus accumulated, he was able to create the realm of Dewachen for the benefit of all beings. Buddha Amitabha was initially an ordinary being who generated Bodhicitta and developed a lot of efforts to achieve Buddhahood. To do this, he practiced the ten paramitas and led them to complete perfection. He also formulated many wishes and aspiration prayers to create this pure land where beings could be reborn easily.

With the completion of paramitas and his aspiration prayers, Amitabha managed to manifest this pure land, the result of a merit accumulated for a long time, expression of very meritorious actions performed in the past. In fact, Buddha Amitabha did not practice in order to attain enlightenment. He followed another approach. At one time, he was a disciple of a Buddha who gave him specific instruction, and explained to him how a great bodhisattva can manifest a pure land beneficial to all beings. Buddha Amitabha, as a disciple, learned all that he needed to do to reach this goal and manifest a pure land able to help the beings trapped in their delusion and enduring suffering due to karma.

Amitabha & Sukhavati. #1 Exposé

Amitabha & Sukhavati. #2 Dialogue

Short Sukhavati Prayer :

É Ma Ho! Amazing!

Amitabha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, with Chenrezig, the Great Compassionate Lord, to his right and Vajrapani, the Bodhisattva of Great Powers, to his left, all surrounded by innumerable Buddhas and Bodhisattvas!

As soon as I have left this existence behind,without the interval of another life, may I take birth in that wondrous Pure Land, the Realm of Joy,the place of everlasting happiness called Dewachen,and may I directly perceive the Buddha of Infinite Light.

O all you Buddhas and Bodhisattvas of the ten directions, please grant your blessings so that the wishes which I have just expressed may be accomplished without any obstacles.

Tayatha Pentsadriya Awa Bodhanayé Soha.

The Wishing Prayer to be reborn in Dewachen (Sukhavati)

Karmapa Thaye Dorje Chants the Sukhavati Prayer

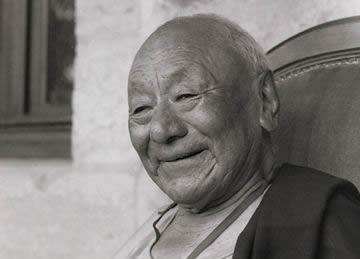

Kunzig Shamar Rinpoche: The world of Dewachen

The Boundless Creativity of Change

Appreciating the Whole Cycle of Impermanence.

We usually appreciate only half of the cycle of impermanence. We can accept birth but not death; accept gain but not loss.

True liberation comes from appreciating the whole cycle and not grasping onto those things that we find agreeable. By remembering the changeability and impermanence of causes and conditions, both positive and negative, we can use them to our advantage. Wealth, health, peace, and fame are just as temporary as their opposites.

If you cannot accept that all compounded or fabricated things are impermanent. If you believe that there is some essential substance or concept that are permanent, you are swimming against the stream of reality.

Consider the example of generosity. When we see everything as transitory and without value, we don’t necessarily have to give it all away, but we have no clinging to it. When we see that our possessions are all impermanent compounded phenomena, that we cannot cling to them forever, generosity is already practically accomplished.

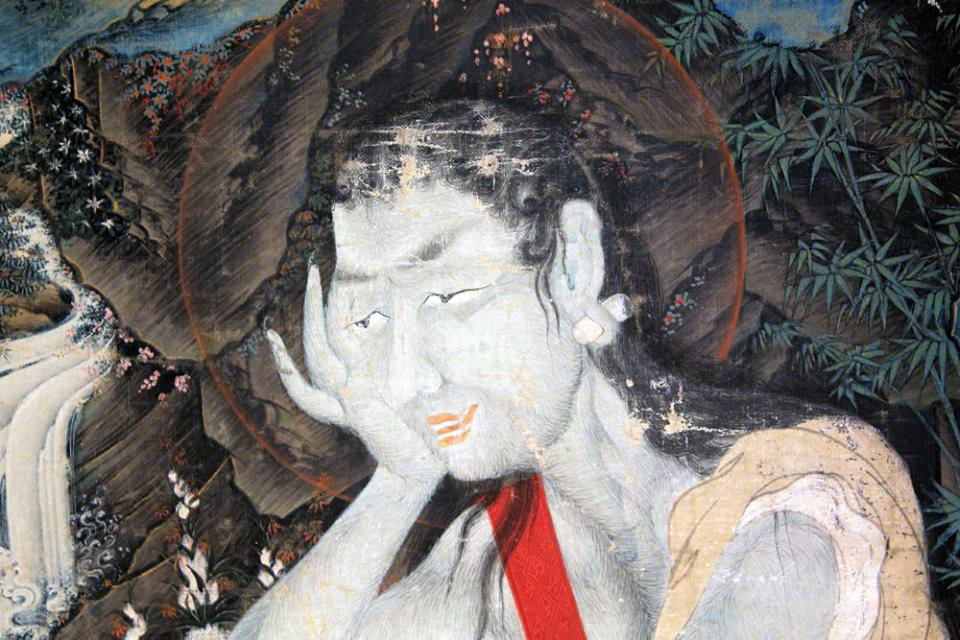

Méditation Guidée vers la Claire Lumière du Sommeil

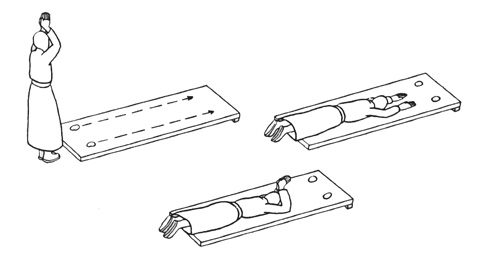

Au moment de l’endormissement l’esprit peut s’établir dans la claire lumière de l’état naturel et purifier les voiles de l’ignorance pendant notre sommeil.

Ce processus étant proche de celui du moment de la mort, il constitue un excellent entrainement.

Lama Tsony

Dialogues sur le Chemin

Série de dialogues sur des thèmes variés chemin faisant.

#1 2020. Les dix points sur lesquels il est bon d’insister de Gampopa

Notre chemin spirituel vers l’éveil ne se fait pas en parallèle de notre vie. L’entraînement de l’esprit nous apprend à « amener la vie à la voie ». Parmi la multitude des instructions, il est bon de trouver la « ligne claire » qui nous permet, par sa simplicité, de trouver la profondeur. Voici, extrait du Précieux rosaire de la voie sublime de Gampopa, dix points sur lesquels il nous faudra insister à mesure que nous progressons.

1. Au début il est nécessaire de mettre l’accent sur l’écoute des enseignements et la réflexion sur leur sens.

2. Quand l’expérience se fait jour, il faut insister sur la pratique de la méditation.

3. Tant que ces expériences ne sont pas stables, il faut privilégier la solitude.

4. Si la dispersion et l’agitation dominent en nous, il faut insister sur les moyens de discipliner la conscience.

5. Si la torpeur et l’opacité mentale dominent en nous, il faut insister sur les moyens d’éclaircir la conscience.

6. Tant que l’esprit n’est pas stable, il faut insister sur l’absorption méditative.

7. S’étant livré à l’absorption méditative, il faut persévérer dans la phase de post méditation.

8. Quand on rencontre de nombreuses circonstances défavorables, il faut mettre l’accent sur la pratique des trois formes de patience.

9. Quand l’attachement et le désir sont très forts, il faut insister sur la pratique du détachement de façon radicale.

10. Si l’amour et la compassion sont très faibles, il faut insister sur l’entraînement de l’esprit d’éveil.

Telles sont les dix points sur lesquels il est bon d’insister.

#2 2021. Un vernis de confusion sur un océan de sagesse

Ayant perdu de vue la Nature de Bouddha qui est la profondeur de la réalité de notre esprit, nous nageons parmi les détritus de nos habitudes et schémas émotionnels. Prenant conscience de la bonne nouvelle de la Nature Bouddha, nous pouvons changer notre perspective et nous enraciner dans la confiance de notre santé fondamentale pour faire face aux défis de la vie avec grâce et discernement. Comme un cygne doré en des eaux tumultueuses.

Un vernis de confusion sur un océan de sagesse #1 Exposé

Un vernis de confusion sur un océan de sagesse #2 Dialogue

#3 Se concentrer sur sa pratique et rester fidèle à soi-même.

Le film rendant hommage à Kunzig Shamar Rinpoché se termine par ces quelques mots du Gyalwa Karmapa Thaye Dorje:

“L’enseignement de l’impermanence est la leçon que tous les êtres, même le Bouddha lui-même, doivent mourir. Je voudrais vous assurer qu’en vous concentrant sur votre pratique, en restant fidèle à vous-même, cela aura un grand, grand avantage. Nous serons tous connectés d’une manière qui transcende les limites de l’espace et du temps. “

Qu’entend-on par rester fidèle à soi même?

Comment se libérer de ce qui nous enferre?

Désir et renonciation ?

Comment vivre les contradictions entre les lois ordinaires, et loi du karma

Se concentrer sur sa pratique et rester fidèle à soi-même #1 Exposé

Se concentrer sur sa pratique.Rester fidèle à soi même. #1 Exposé. Transcription par Bernadette Baijard.Download

Se concentrer sur sa pratique et rester fidèle à soi-même #2 Dialogue

#4 Les moyens d’existence justes

Les Moyens d’existence justes visent à garantir que l’on gagne sa vie d’une manière juste. Pour un disciple laïc, le Bouddha enseigne que la richesse doit être acquise selon certaines normes. Il ne faut l’acquérir que par des moyens légaux ; il faut l’acquérir pacifiquement, sans contrainte ni violence ; il faut l’acquérir honnêtement, pas par la ruse ou la tromperie ; et il faut l’acquérir de manière à ne pas causer de mal et de souffrance à d’autres.

Une vie saine, comme un jardin, nécessite une attention constante. La gratitude et la bienveillance découlent de la compréhension de l’interdépendance de tout. Cela donnera naissance à l’attitude d’esprit éveillée (Skt.Bodhicitta). La présence et la conscience seront nos précieux outils. La culture d’une activité vertueuse et d’un style de vie sain deviendra une évidence. L’herbe des habitudes qui nourrissent l’ego devra être régulièrement déracinée. Quel plaisir, alors, de partager la récolte abondante avec tous les êtres!

Les moyens d’existence justes #1 Exposé

Les moyens d’existence justes #2 Dialogue

Les Quatre Sceaux du Dharma #5

Au-delà de la fascination et du rejet. Un chemin vers la paix transcendant les extrêmes

Nous sommes souvent pris entre la fascination pour les merveilles de la création et le désir de libération. Ils constituent un paradoxe qui conduit à des dissonances cognitives et à des sentiments contradictoires.

Comment résoudre cela afin de trouver une voie menant au-delà de ces extrêmes, contribuant ainsi à notre bien et à celui de tous, en particulier dans notre proche entourage de nos proches comme par exemple nos enfants?

Comment leur montrer la voie en devenant un modèle inspirant?

Les Quatre Sceaux du Dharma sont un moyen d’explorer cela.

ཆོས་ རྟགས་ ཀྱི་ ཕྱག་ རྒྱ་ བཞི་

༈ འདུ་ བྱེད་ ཐམས་ཅད་ མི་ རྟག་ ཅིང༌ །

ཟག་ བཅས་ ཐམས་ཅད་ སྡུག་བསྔལ་ བ །

ཆོས་ རྣམས་ སྟོང་ ཞིང་ བདག་ མེད་ པ །

མྱ་ངན་ ལས་ འདས་ པ་ ཞི་ བའོ ། །

Toutes les choses composées sont impermanentes.

Tous les contacts contaminés sont douloureux.

Le mot tibétain pour les contacts contaminés dans ce contexte est zagche, qui signifie «contaminé» ou «taché», dans le sens d’être imprégné de confusion ou de dualité. L’esprit dualiste englobe presque toutes les pensées que nous avons. Pourquoi est-ce douloureux? Parce que c’est une erreur. Tout esprit dualiste est un esprit erroné, un esprit qui ne comprend pas la nature des choses. Chaque fois qu’il y a un esprit dualiste, il y a de l’espoir et de la peur. L’espoir est une douleur parfaite et systématisée. Nous avons tendance à penser que l’espoir n’est pas douloureux, mais en fait c’est une grande douleur. Quant à la douleur de la peur, ce n’est pas quelque chose qui a besoin de démonstration. Le Bouddha a dit: «Comprenez la souffrance.» Telle est la première Noble Vérité. Beaucoup d’entre nous confondent la douleur avec le plaisir – le plaisir que nous avons maintenant est en fait la cause même de la douleur que nous allons ressentir tôt ou tard. Une autre façon bouddhiste d’expliquer cela est de dire que lorsqu’une grande douleur diminue, nous l’appelons plaisir. C’est ce que nous appelons le bonheur.

Tous les phénomènes sont sans existence intrinsèque.

Le Nirvana est la paix au-delà des extrêmes.

Les Quatres Sceaux du Dharma #1 Exposé

Les Quatres Sceaux du Dharma #2 Dialogue

#6 Le Chemin d’Accumulation

Sur le chemin d’accumulation, les bodhisattvas, ou «héritiers des vainqueurs», génèrent une intention positive et une bodhicitta à la fois en aspiration et en action. Ayant complètement développé cette bodhicitta relative, ils aspirent à la bodhicitta ultime, la sagesse non conceptuelle du chemin de la vue. C’est donc l’étape de la «pratique par aspiration». On l’appelle le chemin de l’accumulation parce que c’est le stade auquel nous faisons un effort particulier pour rassembler l’accumulation de mérite, et aussi parce qu’il marque le début de nombreux éons incalculables de rassemblement des accumulations.

Le chemin de l’accumulation est divisé en étapes inférieures, intermédiaires et supérieures. Au stade inférieur du chemin d’accumulation, il est incertain quand nous atteindrons le chemin de la jonction. Au stade intermédiaire du chemin de l’accumulation, il est certain que nous atteindrons le chemin de la jonction dans la toute prochaine vie. Sur l’étape supérieure du chemin de l’accumulation, il est certain que nous atteindrons le chemin de la jonction au cours de la même vie.

Questions:

Une vie à la fois

Une fois vous avez mentionné, que nous ne devrions pas considérer la mort comme une finalité. C’était un conseil très intéressant. Certains d’entre nous ne peuvent pas faire beaucoup de progrès en une seule vie; parfois je suis tenté d’abandonner un peu.

– Pouvez-vous élaborer sur les objectifs à long et à court terme?

– Quels sont les objectifs réalistes?

– L’aspiration continue, le développement de la stabilité mentale et la génération d’une bienveillance ouverte et accueillante proviennent de vos enseignements comme de bons objectifs.

– Qu’est-ce qui manque, ou le contraire?

– Que faut-il abandonner?

Le Chemin d’accumulation #1 Exposé

Le Chemin d’accumulation #2 Dialogue

#7 Transformer souffrance et bonheur en Éveil

par Dodrupchen Jigmé Tenpé Nyima

Hommage

Je rends hommage au noble Avalokiteśvara, en me rappelant ses qualités :Toujours réjoui du bonheur des autres,Et suprêmement affligé quand ils souffrent,Vous avez pleinement réalisé la « Grande compassion » et toutes ses qualités,Et demeurez, sans le moindre souci pour votre bonheur ou votre souffrance !

Déclaration d’intention

Je vais donner ici par écrit une instruction partielle sur la manière d’utiliser le bonheur et la souffrance comme chemin vers l’Éveil. C’est indispensable pour mener une vie spirituelle, un outil très nécessaire aux êtres nobles, et il n’est pas d’enseignement plus précieux au monde.Il y a deux parties :1) comment utiliser la souffrance comme chemin2) et comment utiliser le bonheur comme chemin.Chacune de ces pratiques est envisagée d’abord sur le plan de la vérité relative, puissur le plan de la vérité absolue.

Transformer souffrance et bonheur en Éveil #1 exposé

Transformer souffrance et bonheur en Éveil #2 Dialogue

#8 Patience et Equanimité

La troisième paramita nous entraîne à être stables et à cœur ouvert face aux personnes et aux circonstances difficiles. La patience implique de cultiver le courage, la pleine conscience et la tolérance. En général, lorsque nous sentons que les autres nous blessent ou nous dérangent, nous réagissons avec diverses formes de colère et d’irritation, cherchant instantanément à riposter. Quand il s’agit de la paramita de la patience, cependant, nous restons aussi inébranlables qu’une montagne, ne cherchant ni à se venger ni à nourrir de profond ressentiment dans nos cœurs. La patience tolérante est un antidote très puissant à la colère.

Les trois catégories de patience sont (A) la patience avec les ennemis, (B) la patience avec les difficultés sur le chemin et (C) la patience avec les hauts et les bas de la vie.

Patience et équanimité #1 Exposé

Patience et équanimité #2 Dialogue

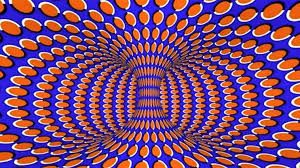

#9 Comment Transformer notre Vision Dualiste par la Prise de Conscience de l’Impermanence.

Comment la reconnaissance de l’éphémère dans la vie quotidienne peut-elle conduire à la réalisation de l’interdépendance et de l’unité de la forme et du vide?

Comment, à l’aide exemples, rechercher des preuves d’impermanence tout au long de notre expérience quotidienne pour contrecarrer notre tendance à solidifier, séparer et figer les objets de notre perception?

Les Douze Exemples d’Illusion:

La magie

La Lune dans l’eau

Une distorsion visuelle

Un mirage

Un rêve

Un écho

La cité des Gandharvas

Une illusion d’optique

Arcs en ciel

Éclair

Bulles d’eau

Reflet dans un miroir

Impermanence et Illusion #1 Exposé

Impermanence et Illusion #2 Dialogue

#10. Le Grand Yoga.Lojong 5:22

VOUS ÊTES BIEN ENTRAÎNÉ SI VOUS POUVEZ MÊME RÉSISTER À LA DISTRACTION.

Lojong 5:22

Au moment d’une pensée négative ou d’une perturbation, si vous pouvez garder votre sang-froid et appliquer naturellement les méthodes pour le maîtriser sans ressentir aucune tension, cela signifie que vous êtes bien entraîné. La correction est assez automatique du fait de votre maîtrise de la pratique. Même au milieu d’un bouleversement, vous pouvez rester calme et continuer à utiliser les conditions immédiates pour vous entraîner. Comme un cavalier expert, vous ne tomberez pas de cheval même si vous êtes distrait.

Être stable dans votre pratique ne signifie pas que vous n’avez plus de saisie du soi. Cela signifie plutôt que lorsqu’il fait surface, il est immédiatement corrigé. Naropa dit un jour à Marpa :

« Ta pratique a atteint un tel niveau que, comme un serpent enroulé, tu es capable de te libérer en un instant. »

Il sera évident que vous avez accompli votre pratique lorsque les cinq grandes qualités de l’esprit apparaîtront :

Bodhicitta : Le premier grand esprit est la bodhicitta. L’effet d’un esprit de bodhicitta dominant et omniprésent est un sentiment complet de satisfaction. Pendant que vous continuez à vous entraîner, votre contentement est si fort que vous n’avez aucun désir d’autre chose.

Excellente maitrise : votre esprit est tellement discipliné que vous remarquez la moindre erreur qui crée une cause négative et la corrigez immédiatement.

Grande patience : Vous avez une énorme patience pour maîtriser vos émotions négatives et vos souillures. Vous n’avez aucune réserve lorsqu’il s’agit de gérer un état d’esprit négatif. En d’autres termes, vous continuez à entraîner votre esprit quoi qu’il arrive.

Grand mérite : lorsque tout ce que vous faites, dites ou pensez vient d’une seule intention – accomplir le bien des autres – alors vous ne faites qu’un avec la pratique du dharma. Simultanément, alors que vous accomplissez votre pratique et vos affaires quotidiennes, le mérite s’accumule continuellement. Cela, à son tour, soutient directement vos activités positives générant toujours plus de mérite. De cette façon, un grand mérite se multiplie automatiquement.

Grand yoga : Le grand yoga (pratique) est la bodhicitta ultime. C’est l’esprit vaste et profond de la sagesse qui expose la nature de la réalité. Posséder et maintenir cette vue parfaite est donc la pratique du dharma par excellence. Grâce à l’entraînement mental, vous atteindrez ces cinq grandes qualités de l’esprit. Vous devez vous entraîner sérieusement pour les développer, car ils ne se produiront pas par des vœux pieux.

Le yoga est un mot complexe avec de nombreuses significations. Dans ce contexte, il convient d’examiner comment le terme est utilisé en tibétain. Le mot tibétain pour le yoga est « Neldjor » (rnal ‘byor). “Nel” est la nature originelle éveillée de l’esprit, le dharmakaya ou la nature de vérité. « Djor » est un verbe qui signifie obtenir ou atteindre. « Neldjor » signifie donc atteindre la nature originelle de l’esprit.

L’apparition des cinq grands esprits prouvera que l’essence de la pratique du bodhisattva est devenue votre nature. Vous ne vous engagerez dans aucune négativité, aussi petite soit-elle. Vous êtes en contrôle et ne pouvez pas être influencé par des émotions négatives. Pour vous, tous les remèdes entrent en action de manière assez automatique même lorsque vous n’y prêtez pas trop d’attention. Pendant que les remèdes sont appliqués, vous restez calme et équilibré. La plupart de votre temps est naturellement consacré à travailler aux autres ou à votre éveil (qui est aussi, en effet, pour les êtres sensibles).

Un point très important est celui-ci : la vraie compassion n’est pas émotionnelle. Les pratiquants mûrs ont une vision claire fondée sur la bodhicitta ultime. Ils connaissent déjà la nature de la souffrance elle-même. Leur compassion est influencée par la sagesse, il n’y a donc aucune tristesse ou émotion impliquée. Sans entrave et libre d’émotions, les bodhisattvas aident les autres de manière sensée et appropriée.

Six Vers du Gourou Yoga

Gyalwa Karmapa IX

“Précieux maître, je vous adresse ma prière.

Accordez votre bénédiction afin que mon esprit abandonne sa saisie d’un soi.

Accordez votre bénédiction afin que je n’éprouve pas de besoin (attachement).

Accordez votre bénédiction afin que cessent les pensées qui ne participent pas du Dharma.

Accordez votre bénédiction afin que soit réalisée la nature non-née de l’esprit.

Accordez votre bénédiction afin que l’illusion se dissipe d’elle-même.

Accordez votre bénédiction afin que la manifestation soit actualisée comme le corps de la réalité.”

Le Grand Yoga. #1 Exposé

Le Grand Yoga. #2 Dialogue

Prières mentionnées durant notre dialogue.© https://thouktchenling.net/

2022 #1 Vaincre les Klesha

Trois angles d’approche du sujet

1/Par la détermination à préserver les voeux d’éthique

Premièrement : Évaluez la réalité de la souffrance et abandonnez l’effort constant de la nier en une quête sans fin de l’objet idéal.

“La vie oscille comme un pendule d’avant en arrière entre la douleur et l’ennui.”

Selon Schopenhauer, la souffrance est le fond de l’existence humaine : c’est souffrance d’exister provient du fait que l’homme, cette machine à désirer, est sans cesse déçu de ses satisfactions. Dès qu’un désir est satisfait, il vient d’autres désirs, qu’il faudra bien accomplir. C’est la Volonté de vivre, l’instinct autrement dit, qui nous fait désirer. Mais dès que l’on tue en nous le désir, c’est l’ennui qui pointe, le vide du coeur. Ainsi, l’homme est déchiré entre cette double menace, ce qui constitue une source certaine de son malheur.

Deuxièmement : S’appuyer sur les vœux du refuge et de libération individuelle (Pratimoksha) pour défaire les habitudes toxiques tout en nourrissant la spirale vertueuse menant à l’éveil.

2/Par l’amour et la compassion illimités.

Instructions Essentielles sur Tonglen de Khenpo Munsel

“Khenpo Munsel m’a donné de nombreuses instructions orales spéciales sur le tong-len qui n’étaient pas dans le texte. Par tong-len, généralement, nous disons que nous envoyons du bonheur aux autres et prenons en charge la souffrance des autres.

Mais pour le sens réel de tong-len, vous devez comprendre l’inséparabilité de soi et de l’autre. Le fondement de nos esprits est le même. Nous comprenons cela à partir de la vue.

Dans ce contexte, même s’il existe de nombreux types de souffrances différentes, il n’y a qu’une seule chose appelée “souffrance”. Il n’y a qu’une souffrance, enseigna-t-il. S’il n’y a vraiment qu’une seule souffrance, alors à ce moment où vous souffrez vous-même d’une grande souffrance, vous devriez penser : « L’esprit des êtres sensibles des trois royaumes et mon esprit ont le même fondement. » Cependant, l’essence de la souffrance des êtres sensibles des trois royaumes et l’essence de notre propre souffrance est la même.

Si vous les voyez comme étant les mêmes, si vous les voyez comme non duels, puis méditez sur cette souffrance, dans l’état naturel de l’esprit, cette souffrance s’en va.

À ce moment-là, vous avez été en mesure d’atténuer la souffrance de tous les êtres sensibles des trois royaumes, d’un seul coup.

Le “len” de tong-len signifie “prendre”. Tout d’abord, prenez de cette façon. “Tong” signifie “donner”. Si vous comprenez la nature de votre esprit, alors vous reconnaissez l’essence de toutes les émotions de souffrance et d’affliction qu’il peut y avoir dans la vacuité.

Lorsque la souffrance ne vous fait plus de mal, l’esprit jouit d’une grande félicité. Si à ce moment-là, vous méditez, en vous rendant vous-même et les autres inséparables, alors cette béatitude peut diminuer la saisie du soi de tous les êtres sensibles. Cela peut diminuer la saisie de soi.

Le bonheur qui est donné est le celui qui provient de la pratique du don et de la prise en charge.

C’est ainsi que vous devez pratiquer. C’est très spécial. D’autres ne l’expliquent pas de cette façon.”

Garchen Rinpoché

3/Par la profondeur du discernement.

Assimiler les afflictions à la pratique

Extrait de : Shamar Rinpoché. “Au cœur de la sagesse: Manuel de la pratique du mahāmudrā.”

Même s’il est dit qu’il existe 84 000 afflictions, elles sont en fait indénombrables. Elles sont généralement catégorisées en cinq groupes : l’attachement, la colère, l’ignorance, la jalousie et l’orgueil. Quand vous les intégrez à votre pratique en reconnaissant leur véritable nature, l’ensemble des 84 000 afflictions est résolu en un instant. À ce moment, la nature de bouddha se révèle spontanément sous la forme des cinq aspects de sagesse. Il s’agit du résultat significatif de l’assimilation des afflictions à la méditation. La nature fondamentale de l’esprit est sagesse pure. En d’autres termes, les cinq formes de sagesse sont la nature innée de l’esprit, communément appelée la nature de bouddha. Lorsque l’esprit est voilé par l’ignorance, ces qualités pures sont masquées et elles nous apparaissent comme les cinq groupes d’afflictions alors qu’en réalité, elles sont cinq formes de sagesse. Par conséquent, la véritable nature de toutes les afflictions n’est pas différente de la véritable nature de l’esprit. Si nous comprenons que l’esprit et toutes ses afflictions sont intrinsèquement vides et non nés, l’ignorance est éradiquée en un instant.

Les afflictions sont parfois connues comme des poisons alors que la sagesse est décrite comme du nectar. C’est la raison pour laquelle l’instruction au sujet de l’assimilation des afflictions à la méditation est appelée l’instruction sur la transformation du poison en nectar.

La première affliction est l’attachement. Lorsque la nature intrinsèque de l’attachement est reconnue comme vide et non née, elle se révèle comme la sagesse discernante. Cette sagesse connaît toute chose distinctement et telle qu’elle est. Un bouddha sait intuitivement comment et pourquoi les choses sont telles qu’elles sont ; c’est tout ce que l’on peut dire au sujet de la sagesse d’un bouddha. Il est dit que lorsqu’un bouddha regarde la queue d’un paon, il peut expliquer instantanément les causes et les conditions karmiques qui ont provoqué les différentes couleurs de chaque plume.

La seconde affliction est la colère. Lorsque la vraie nature de la colère est reconnue, la colère s’actualise en la sagesse de la vaste étendue, la sagesse du dharmadhātu. Chaque expérience est alors reconnue comme indissociable de la vacuité, la véritable nature de l’esprit. En l’état de vacuité de l’esprit, chaque expérience est une expérience d’espace ; chaque phénomène se manifeste dans l’étendue omnipénétrante et la qualité libératrice de l’éveil.

La troisième affliction est l’ignorance. Lorsque la nature innée de l’ignorance est reconnue comme vide et non née, elle se révèle comme la sagesse semblable au miroir, parfois appelée la sagesse omnisciente. Il n’existe aucune limite à la connaissance dans l’omniscience, ni en terme d’espace ni en terme de temps. Une personne ordinaire ne peut percevoir les choses que de manière séquentielle. Un bouddha, cependant, connaît tout de manière instantanée et simultanée. Tout ce qui apparaît dans son esprit est clair et précis, sans hésitation ni obstruction. Tout phénomène est perçu aussi directement qu’une image dans un miroir. Par ailleurs, les objets solides n’opposent aucune résistance à un individu qui peut ainsi voir à travers un mur et même passer au travers s’il le décide.

La quatrième affliction est l’orgueil ou la saisie égotique. Il s’agit de la discrimination que vous opérez entre vous-mêmes et les autres. Dans une situation particulière, en général vous vous favorisez par rapport aux autres. Dans l’état éveillé, l’orgueil est actualisé en la sagesse non discriminante, aussi appelée sagesse d’égalité. Vous réalisez que toute chose est indissociable dans la vacuité de l’esprit parce que tout est pareillement vide.

La cinquième affliction est la jalousie. En l’état éveillé, la jalousie est révélée comme la sagesse tout accomplissante, la sagesse d’activité. Un bouddha est le mieux placé pour aider tous les êtres sensibles, car il connaît leurs souhaits, leurs capacités et leurs habiletés. Bouddha est ici utilisé dans le sens large du terme et n’est pas confiné à un bouddha historique spécifique.

Les afflictions sont semblables à des poisons tant qu’elles ne sont pas révélées comme sagesse. La technique pour assimiler les afflictions à la pratique est exactement la même que pour l’intégration des pensées à la pratique.

Tout d’abord, prenez conscience de l’apparition d’une affliction et identifiez-la. Ensuite, regardez sa nature. Puis, renoncez à votre attachement au ressenti. Enfin, ne soyez ni inquiets ni optimistes à propos du résultat, mais acceptez toute éventualité avec courage et confiance.

Comportez-vous comme un lion face aux épreuves et aux difficultés. Soyez libres d’attachements comme le vent qui souffle dans le ciel. Comportez-vous comme un fou, sans faux-semblants ni artificialité. Cette même technique s’applique à toutes les afflictions.

Parmi ces cinq afflictions, certaines sont plus faciles à détecter et à identifier que d’autres. La colère, par exemple, est habituellement facile à repérer. La jalousie et l’attachement ne sont pas non plus très dissimulés. Cependant, lorsque vous êtes gonflés d’orgueil ou minés par l’ignorance, vous ne remarquez généralement pas leur présence. Votre mode de pensée égotique est un schéma habituel tellement ancré, que l’éradiquer demande du temps et de la patience. Quand vous êtes ignorants, vous n’êtes souvent pas assez intelligents pour le savoir ! En revanche, dès que vous aurez travaillé avec des afflictions plus apparentes, vous pourrez appréhender, pendant la pratique, celles qui s’avèrent plus dissimulées.

Un méditant très avancé éprouve parfois de grandes difficultés à trouver la façon et le moyen d’approfondir sa pratique et son accomplissement. Ainsi, après avoir réussi à assimiler les afflictions à la méditation en reconnaissant leur véritable nature, il peut continuer en générant délibérément des afflictions encore plus fortes, afin de donner du dynamisme à sa pratique. En faisant cela, le méditant amène sa pratique vers un degré d’accomplissement plus élevé. Son comportement odieux peut être outrageant ; c’est bien compréhensible. En effet, rien ne permet de déterminer qu’il s’agisse d’un méditant avec une motivation pure qui pratique l’actualisation des afflictions en degrés de réalisation. Marpa était un bon exemple de pratiquant engagé dans cette forme de pratique. En plus d’être un éminent enseignant et traducteur, il était aussi propriétaire foncier. Les personnes qui interagissaient avec lui à un niveau concret le considéraient comme un individu très désagréable, fier et orgueilleux, avec une insatiable cupidité. Cependant, le grand mahasiddha érudit Naropa (1016–1100) lui dit un jour :

Les autres vous considèrent comme ayant de très fortes afflictions. Cependant, dans votre esprit, une affliction est comme un serpent que l’on aurait noué. Il se dégage en moins de temps qu’il ne faut pour faire le nœud.

Certains lamas au Tibet étaient connus pour se comporter comme Marpa, dans l’espoir d’induire les gens à penser qu’ils avaient atteint des niveaux exaltés où les fortes négativités de l’esprit constituaient du carburant pour leur pratique. Ils s’adonnaient gratuitement à une vie de débauche. Cependant, sans l’accomplissement de Marpa, ces comportements étaient uniquement nuisibles. Sans aucune utilité pour la pratique, ils ne devaient en aucun cas être considérés comme une indication de grand accomplissement. Leur comportement était peut-être semblable à celui de Marpa, mais ils étaient loin d’être aussi réalisés que lui.

Première Partie: Par la détermination à préserver les voeux d’éthique

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

Seconde Partie: Par l’amour et la compassion illimités.

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

Troisième Partie: Par la profondeur du discernement.

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

2022 #4 L’accompagnement sur le Chemin Spirituel

Quelle est la place de la tradition et des ami(e)s spirituel(le)s dans notre monde actuel?

Un jour, Ananda et le Bouddha étaient assis seuls sur une colline, surplombant les plaines du Gange. Ayant servi comme serviteur du Bouddha pendant de nombreuses années, Ananda partageait souvent ses réflexions et ses idées avec lui. Cet après-midi, Ananda a pris la parole. “Cher Maître Respecté,” dit Ananda. « Il me semble que la moitié de la vie spirituelle est une bonne amitié, une bonne compagnie, une bonne camaraderie. » Mais le Bouddha le corrigea rapidement : « Non pas, Ananda ! Ce n’est pas le cas, Ananda ! » Il poursuivit : « C’est toute la vie spirituelle, Ananda, c’est-à-dire une bonne amitié, une bonne compagnie, une bonne camaraderie. Quand un moine a un bon ami, un bon compagnon, un bon camarade, il faut s’attendre à ce qu’il développe et cultive la noble voie octuple. » Le Bouddha a habilement corrigé l’idée d’Ananda selon laquelle la sangha et le dharma sont séparés. L’un n’est pas la moitié de l’autre ; la sangha n’est pas simplement utile pour réaliser le chemin. La sangha est le chemin. L’amitié spirituelle est le chemin.

Kalyana Mitra

En sanskrit, Kalyana Mitra signifie « ami spirituel ». Kalyana peut être traduit par « bon, vrai, vertueux, droit ou bénéfique », et Mitra est la racine du mot maitri, qui signifie gentillesse. Un Kalyana Mitra est quelqu’un qui vous aide à réaliser vos aspirations profondes, quelqu’un qui élève votre chemin vers un niveau supérieur de bien-être éthique et spirituel avec une gentillesse désintéressée.

Beaucoup de gens, devant tant d’enseignements faisant l’éloge de la pratique de la méditation et de la solitude, pensent que le bouddhisme est une pratique pour les solitaires. Mais les encouragements du Bouddha à pratiquer dans la solitude étaient contrebalancés par un ardent accent mis sur la culture d’amitiés dignes. Tout au long de sa carrière d’enseignant, le Bouddha a parlé à maintes reprises de l’importance cruciale des Kalyana Mitras pour réussir dans sa pratique, déclarant qu’il n’y a pas d’autre facteur aussi propice à l’émergence de la noble voie octuple que la bonne amitié. « Tout comme l’aube est le précurseur du lever du soleil, la bonne amitié est le précurseur de l’émergence du noble octuple sentier », a déclaré le Bouddha. Le « Discours sur le bonheur », qui vante les trente-deux bienfaits d’une vie heureuse, commence par « Éviter les personnes insensées et vivre en compagnie des sages… c’est le plus grand des bonheurs ».

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

2022#5 Trouvez la libération par la réflexion et l’analyse.Lodjong 7/55

Nos esprits ont deux capacités liées : regarder les choses en général et examiner les détails. En tibétain, on les appelle tokpa et chöpa. La première, c’est comme identifier une forêt ; la seconde revient à examiner les arbres de cette forêt.

Nous devrions appliquer ces facultés pour comprendre nos émotions perturbatrices. Par exemple, si vous remarquez que vous vous sentez bouleversé, vous pouvez demander : pourquoi est-ce que je me sens bouleversé ? Parce que j’ai été insulté. Qu’est-ce qui a été dit qui m’a fait me sentir si insulté? Pourquoi cela m’a-t-il insulté, alors que cela n’a pas insulté mon ami ? Examinez la situation sous tous les angles : de votre point de vue, du point de vue de l’autre, du point de vue dharmique, du point de vue mondain, en relation avec le passé, le présent et le futur. Apprenez tout ce qu’il y a à savoir sur le sujet et allez au fond des choses. Une fois que la lumière de votre intelligence critique brillera pleinement, il vous sera facile de vous libérer en appliquant les pratiques du Lojong telles que le tonglen.

Il est important de faire cette pratique systématiquement, en allant du général au spécifique, sans brûler les étapes. Si vous sautez d’un thème général à un autre, ou d’un détail à un autre, vous n’apprendrez pas grand-chose. Vous demeurerez dans le flou. Ce processus demande des efforts et peut vous faire sortir de votre zone de confort. Mais c’est un processus que vous pouvez maîtriser, que vous soyez un intellectuel ou un artiste, que vous soyez éduqué ou non. Il s’agit d’utiliser votre intelligence émotionnelle innée pour comprendre votre propre expérience. Apprendre à appliquer ces deux facultés mentales vous rendra confiant et autonome. Vous serez en mesure de comprendre profondément l’esprit à partir de votre propre expérience. De cette façon, vous deviendrez un excellent enseignant pour vous-même, ainsi que bénéfique aux autres.

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

2022#6. Prières et Mantra

L’importance et les bienfaits de la récitation des mantras.

L’importance de la prière (sans tomber dans un fonctionnement dualiste ou théiste.)

Comment développer la confiance dans la réalité de la présence et de l’aide des déités.

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

2022#7. Confiance et Contrôle

#1. Exposé

#2. Dialogue

2022#8. Renoncement

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

Dharma Roadside Dialogues Series

Series of dialogue on various themes as we walk the path towards home.

#1 Calm Mind in Turbulent Times

Zoom Session given in Austria 12-12-2020

Calm mind in turbulent times. #1 The talk

Calm mind in turbulent times. #2 questions and answers

#2 A thin veneer of confusion on an ocean of wisdom

Zoom session from Bodhi path Natural Bridge, VA. USA

Having lost sight of the Buddha Nature which is the depth of reality in our mind, we swim among the rubbish of our emotional habits and patterns. Realizing the good news of our Buddha Nature, we can change our perspective and become rooted in the confidence of our basic sanity to face life’s challenges with grace and discernment. Like a golden swan in turbulent waters.

A thin veneer of confusion on an ocean of wisdom #1 Expose

A thin veneer of confusion on an ocean of wisdom #2 Dialogue

#3 Focus on your practice and remain true to yourself.

The film paying homage to Kunzig Shamar Rinpoche ends with these few words from Gyalwa Karmapa Thaye Dorje:

“The teaching of impermanence is the lesson that all beings even the Buddha himself must pass. I would like to assure you that, by focusing on your practice, staying true to yourself, this will have great, great benefit. We will be all connected in ways that transcend the boundaries of space and time.”

What do we mean by staying true to oneself?

Are they many ways to free oneself from what binds us?

Desire and renunciation?

How to live the contradictions between ordinary laws, and the law of karma?

Focus on your practice and remain true to yourself. #1 Exposé

Focus on your practice and remain true to yourself. #2 Dialogue

#4. Czech & Slovak Dialogue

Self directed compassion

Building up an healthy self

Steady practice but flexible Mind, or “butterflying”

“Without patience no virtue is possible, patience is the greatest virtue” Atisha

#5 Right Livelihood.

Right Livelihood #1 Exposé

Right Livelihood #2 Dialogue

Further readings:

Mindfulness and Meaningful Work: Explorations in Right Livelihood

#6 The Four Seals of Dharma

Beyond fascination and rejection, a path to peace transcending extremes

We are often caught between the fascination for the marvels of creation and the desire of liberation. They constitute a paradox that leads to cognitive dissonance and contradictory feelings.

How can we resolve this in order to find a way leading beyond these extremes, therefore contributing to our benefit and that of all, in particular in our close circle of near and dear like our children?

How to show them a way becoming an inspiring role model?

The Four Seals of Dharma are a way to explore this.

ཆོས་རྟགས་ཀྱི་ཕྱག་རྒྱ་བཞི་

༈ འདུ་བྱེད་ཐམས་ཅད་མི་རྟག་ཅིང༌།

ཟག་བཅས་ཐམས་ཅད་སྡུག་བསྔལ་བ།

ཆོས་རྣམས་སྟོང་ཞིང་བདག་མེད་པ།

མྱ་ངན་ལས་འདས་པ་ཞི་བའོ། །

All compounded things are impermanent.

All contaminated contacts are painful.

The Tibetan word for contaminated contacts this context is zagche, which means “contaminated” or “stained,” in the sense of being permeated by confusion or duality. The dualistic mind includes almost every thought we have. Why is this painful? Because it is mistaken. Every dualistic mind is a mistaken mind, a mind that doesn’t understand the nature of things. Whenever there is a dualistic mind, there is hope and fear. Hope is perfect, systematized pain. We tend to think that hope is not painful, but actually it’s a big pain. As for the pain of fear, that’s not something we need to explain. The Buddha said, “Understand suffering.” That is the first Noble Truth. Many of us mistake pain for pleasure—the pleasure we now have is actually the very cause of the pain that we are going to get sooner or later. Another Buddhist way of explaining this is to say that when a big pain becomes smaller, we call it pleasure. That’s what we call happiness.

All phenomena are without inherent existence.

Nirvana is peace beyond extremes.

The Four Seals of Dharma #1 Exposé

The Four Seals of Dharma #2 Dialogue

#7 Meditation advices. Czech & Slovak Dialogue

#8. The Path of Accumulation

On the path of accumulation, the bodhisattvas, or ‘heirs of the victorious ones’, generate positive intention and bodhicitta in both aspiration and action. Having thoroughly developed this relative bodhicitta, they aspire towards the ultimate bodhicitta, the non-conceptual wisdom of the path of seeing. This is known, therefore, as the stage of ‘aspirational practice’. It is called the path of accumulation because it is the stage at which we make a special effort to gather the accumulation of merit, and also because it marks the beginning of many incalculable eons of gathering the accumulations.

The path of accumulation is divided into lesser, intermediate and greater stages. On the lesser stage of the path of accumulation, it is uncertain when we will reach the path of joining. On the intermediate stage of the path of accumulation, it is certain that we will reach the path of joining in the very next lifetime. On the greater stage of the path of accumulation, it is certain that we will reach the path of joining within the very same lifetime.

Questions:

One lifetime at a time

Once you have mentioned we should not take death as a deadline. It was very interesting advice. Some of us cannot make a lot of progress in one lifetime; sometimes I’m tempted to give up little bit.

– Can you elaborate about the long term and short-term goals?

– What are realistic goals?

– Continuous aspiration, developing mental stability and generating open welcoming benevolence comes from your teachings as good goals.

– What is missing, or opposite?

– What should be abandoned?

The Path of Accumulation #1 Exposé

The Path of Accumulation #2 Dialogue

#9 Transforming Suffering and Happiness into Enlightenment

by Dodrupchen Jigme Tenpe Nyima

Homage

I pay homage to Noble Avalokiteśvara, recalling his qualities:Forever joyful at the happiness of others,And plunged into sorrow whenever they suffer,You have fully realized Great Compassion, with all its qualities,And abide, without a care for your own happiness or suffering!

Statement of Intent

I am going to put down here a partial instruction on how to use both happiness and suffering as the path to enlightenment. This is indispensable for leading a spiritual life, a most needed tool of the Noble Ones, and quite the most priceless teaching in the world.

There are two parts:

1) how to use suffering as the path,

2) and how to use happiness as the path.

Each one is approached firstly through relative truth, and then through absolute truth.

Transforming Suffering and Happiness into Enlightenment #1 Exposé

Transforming Suffering and Happiness into Enlightenment #2 Dialogue

#10. Patience and Equanimity

The third paramita trains us to be steady and openhearted in the face of difficult people and circumstances. Patience entails cultivating skillful courageousness, mindfulness, and tolerance. In general, when we feel that others are hurting or inconveniencing us, we react with various forms of anger and irritation, instantly looking to strike back. When it comes to the paramita of patience, however, we remain as unwavering as a mountain, neither seeking revenge nor harboring deep resentment inside our hearts. Patient tolerance is a very powerful antidote to anger.

The three categories of patience are (A) patience with enemies, (B) patience with hardships on the path, and (C) patience with the ups and downs of life.

Patience and equanimity #1 Exposé

Patience and equanimity #2 Dialogue

#11.How to Transform our Dualistic Vision by the Awareness of Impermanence

How can the recognition of transitoriness in daily life bring about the realization of interconnectedness and the unity of form and emptiness?

How to look, with the help of examples, for evidence of impermanence throughout our daily experience to oppose our tendency to solidify, separate and freeze the objects of our perception?

Twelve Examples of Illusion:

Magic

The Moon in the Water

A Visual Distortion

A Mirage

A Dream

An Echo

The City of Gandharvas

An Optical Illusion

Rainbows

Lightning

Water Bubbles

Reflection in a Mirror

Impermanence and Illusion#1Exposé

Impermanence and Illusion #2 Dialogue

#12. The Great Yoga. Lojong 5:22

YOU ARE WELL TRAINED IF YOU CAN EVEN WITHSTAND DISTRACTION.

Lojong 5:22

In the moment of a negative thought or disturbance, if you can maintain your composure and naturally apply the methods to subdue it without feeling any strain, then this means you are well trained. The correction is quite automatic owing· to your proficiency in practice. Even in the midst of an upheaval, you can remain composed and continue to use the immediate conditions to train. Like an expert rider, you ·won’t fall off the horse even when distracted.

Being stable in your practice does not mean that you no longer have any self-grasping. Rather, it means that when it does surface it is remedied right away. Naropa once said to Marpa:

“Your practice has attained to such a level that, like a coiled snake, you are able to release yourself in an instant.”

It will be evident that you have accomplished your practice when the five great qualities of mind arise:

Bodhicitta: The first great mind is bodhicitta. The effect of a dominant and pervasive bodhicitta mind is a complete feeling of satisfaction. While you continue to train, your contentment is so strong that you have no desire for anything else.

Great taming: Your mind is so tame that you notice the tiniest mistake which creates a negative cause and correct it immediately.

Great patience: You have enormous patience to subdue your negative emotions and defilements. You have no reservation whatsoever when it comes to dealing with a negative state of mind. In other words, you continue to train your mind no matter what.

Great merit: When everything you do, say, or think comes from one intention- to benefit others- then you are one with the dharma practice. Simultaneously, as you perform your daily practice and affairs, merit is accumulating continuously. That, in turn, directly supports your positive activities generating ever more merit. In this way, great merit multiplies automatically.

Great yoga: The great yoga (practice) is ultimate bodhicitta. It is the vast and profound mind of wisdom that exposes the nature of reality. To possess and sustain this perfect view is thus the quintessential dharma practice. Through Mind Training you will achieve these five great qualities of mind. You have to earnestly train to develop them, as they will not come about through wishful thinking.

Yoga is a complex word with many meanings. In this context, it is appropriate to examine how the term is used in Tibetan. The Tibetan word for yoga is “Neldjor” (rnal ‘byor). “Nel” is the original awakened nature of mind, the dharmakaya or truth nature. “Djor” is a verb that means to reach or attain. “Neldjor”, therefore, means to reach the original nature of mind.

The arising of the five great minds will prove that the essence of the bodhisattva practice has become your nature. You will not engage in any negativity no matter how small. You are in control and cannot be swayed by negative emotions. For you, all the remedies go into operation quite automatically even when you are not paying too much attention. As the remedies are being applied, you remain calm and balanced. Most of your time is naturally spent working for others or for your enlightenment (which is also, in effect, for sentient beings).

One very important point is this: true compassion is not emotional. Mature practitioners have a clear view grounded in ultimate bodhicitta. They already know the nature of suffering itself. Their compassion is influenced by wisdom so there is no sadness or emotion involved. Unhampered and free of emotions, bodhisattvas help others in a sensible and appropriate way.

Guru Yoga Six Verses

Gyalwa Karmapa IX

I supplicate the precious Lama,

Bestow your blessing to abandon self-grasping.

Bestow your blessing to be continuously free from wants and desires.

Bestow your blessing to stop doubts, and mistrust in the dharma.

Bestow your blessing that I realize the mind to be beyond birth, cessation and dwelling.

Bestow your blessing that confusions are pacified into themselves.

Bestow your blessing that existence is realized to be dharmakaya.

#13. Czech & Slovak Dialogue

What to do with the attachment to the methods of liberation?

Stand for your right and the art of negotiation.

Planning and mindfulness.

Conscientiousness in getting rid of the klesha.

Does Vajrasattva clean it all?

2022 #1 Defeat the Klesha

Three angles of approach to the subject

1/By the determination to preserve the ethical commitments

Firstly: Assess the reality of suffering, and let go of the constant effort to deny it in an endless quest for the ideal object.

“Life swings like a pendulum backward and forward between pain and boredom.”

According to Schopenhauer, suffering is the basis of human existence: it is suffering to exist comes from the fact that man, this machine to desire, is ceaselessly disappointed with his satisfactions. As soon as a desire is satisfied, there come other desires, which must be fulfilled. It is the Will to live, in other words instinct, which makes us desire. But as soon as we kill desire in us, it is boredom that emerges, the emptiness of the heart. Thus, man is torn between this double threat, which constitutes a certain source of his misfortune.

Secondly: Rely on refuge and individual liberation vows (Pratimoksha) to break toxic habits while nurturing the virtuous spiral leading to enlightenment.

2/By unlimited love and compassion

Khenpo Munsel Tonglen Pith instructions

“Khenpo Munsel gave me many special oral instructions on tong-len that weren’t in the text. In tong-len, generally, we say that we are sending happiness out to others and taking others’ suffering in.

But for the actual meaning of tong-len, you have to understand the inseparability of self and other. The ground of our minds is the same. We understand this from the View.

In this context, even if there are many different types of suffering, there is only one thing called “suffering”. There is only one suffering, he taught. If there is really only one suffering then at this time when you, yourself, have great suffering, you should think, “The minds of the sentient beings of the three realms and my mind have the same ground.” However, the essence of the suffering of the sentient beings of the three realms and the essence of our own suffering is the same.

If you see them to be the same, if you see them as being non-dual, and then meditate on that suffering, in the mind’s natural state, that suffering goes away.

At that moment, you have been able to lessen the suffering of all sentient beings of the three realms, all at once.

The “len” of tong-len means “taking.” First, take in this way. “Tong” means “giving.” If you understand your mind’s nature, then you recognize the essence of whatever suffering and afflictive emotions there may be to be emptiness.

When suffering does not harm you anymore, the mind has great bliss. If at that time, you meditate, making self and others inseparable, then that bliss can diminish the self-grasping of all sentient beings. It can lessen the self-grasping.

The happiness that is being given is the bliss that comes from the practice of giving and taking.

This is how you should practice. This is very special. Others don’t explain it this way.”

Garchen Rinpoche

3/By the depth of discernment

Turning Afflictions into Practice

Excerpt From: Shamar Rinpoche. “Boundless Wisdom: A Mahāmudrā Practice Manual.”

Although it is said that there are 84,000 afflictions, in fact they are beyond enumeration. Broadly speaking, they can be generalized into five groups: attachment, anger, ignorance, jealousy, and pride.

When you turn them into practice by recognizing their true nature, all 84,000 afflictions are resolved in an instant. At that moment, Buddha nature reveals itself spontaneously in the five forms of wisdom. That is the far-reaching result of turning afflictions into meditation. The fundamental nature of mind is pure wisdom. In other words, the five forms of wisdom are the innate nature of mind, commonly known as Buddha nature. When the mind is obscured by ignorance, these pure qualities are distorted, and they appear in us as the five forms of affliction. In reality, they are the five forms of wisdom. Thus, the true nature of all afflictions is in no way different from the true nature of mind. If we can only see that the mind and all its afflictions are intrinsically empty and unborn, ignorance will be eradicated in an instant.

Afflictions are sometimes known as poisons, while wisdom is described as nectar. For this reason, the instruction on turning afflictions into meditation is called the instruction on transforming poison into nectar.

The first of the afflictions is attachment. When the intrinsic nature of attachment is recognized as empty “and unborn, it reveals itself as discerning wisdom. In discerning wisdom, all things are perceived distinctly, as they truly are. This is as much as one can say about a Buddha’s wisdom, that a Buddha intuitively knows how and why things are the way they are. It is said that when a Buddha looks at the tail of a peacock, he can instantaneously tell what karmic causes and conditions have brought about all the different colors in each feather.

The second affliction is anger. When the true nature of anger is recognized, anger reveals itself as the wisdom of the expanse, dharmadhātu wisdom. This is when every experience is recognized as inseparable from emptiness, mind’s true nature. In the emptiness of mind, every experience is an experience of spaciousness. In the emptiness of mind, every arising phenomenon occurs within the all-encompassing expanse and liberating quality of awakening.

The third affliction is ignorance. When the innate nature of ignorance is recognized as empty and unborn, it reveals itself as mirror-like wisdom, sometimes known as all-knowing wisdom. There are no limits to knowledge in omniscience, neither “In enlightenment, pride is transformed into the wisdom of nondiscrimination, also called the wisdom of equality. You realize that in the emptiness of mind, all things are undifferentiated in that they are equally empty.”

The fourth affliction is pride, or ego clinging. It is the discrimination between self and others. In any given situation, we generally favor ourselves over others. In enlightenment, pride is transformed into the wisdom of nondiscrimination, also called the wisdom of equality. You realize that in the emptiness of mind, all things are undifferentiated in that they are equally empty.

The fifth affliction is jealousy. In enlightenment, jealousy is transformed into task-accomplishing wisdom, the wisdom of activity. A Buddha, knowing the wishes, capacities, and abilities of all sentient beings, is best able to help them. Here, the term Buddha is used in the broadest sense, and is not confined to a specific historical Buddha.

The afflictions are like poisons for as long as they are not transformed into wisdom. The technique for turning the afflictions into practice is exactly the same as for turning thoughts into practice.

First of all, be aware of the arising of an affliction and identify it; look at its nature. Then relinquish all attachment to the feeling. Finally, do not be apprehensive or hopeful regarding the outcome, but accept any eventuality with courage and confidence.

Be like a lion in the face of hardship and difficulties. Be as free from attachments as the wind blowing through the sky. Be like a madman, without false pretenses and artificiality. The same technique is applicable for all afflictions.

Among the five afflictions, some are easier to detect and identify. Anger, for instance, is usually easy to see. Jealousy and attachment are also not well hidden. However, when you are beset by pride and ignorance, you do not usually know they are there. To be self-centered in our thinking is such an ingrained habitual tendency that it takes both time and patience to eradicate it. When you are ignorant, you are not always intelligent enough to know it. However, once you have dealt with the more apparent afflictions, you will also be able to deal with the more hidden ones in the course of practice.

Sometimes a very advanced meditator has a great deal of difficulty in finding ways and means to further his or her practice and realization. So, after successfully turning the afflictions into meditation by recognizing their true nature, an advanced meditator may go further by deliberately generating even stronger afflictions in order to give impetus to his or her practice. In so doing, the meditator takes the practice to a higher level of realization. People may be understandably outraged by this person’s obnoxious behavior. The reason is that there is no way they can tell that a meditator with pure motivation is practicing the transformation of afflictions into higher realizations.

Marpa was a good example of a practitioner engaging in this kind of practice. Apart from being a great teacher and translator, Marpa was a landowner. People who had practical dealings with him considered him to be a very disagreeable person, proud and aggressive, with insatiable greed. However, the great scholar and mahasiddha Naropa once said to him:

“Other people see you as having very strong afflictions. However, in your mind, an affliction is like a snake twisted into a knot. It straightens itself out in less time than it took to tie itself into the knot.”

Some lamas in Tibet were known to behave like Marpa in the hopes of misleading people into thinking that they were on the exalted level where strong negativity of mind was fuel to their practice. They indulged themselves wantonly in loose living.

But without Marpa’s realization, their behavior was only harmful. It did not help their practice and certainly should not have been seen as an indication of high realization. They might have behaved like Marpa, but they were not highly realized like him.

First Part: By the determination to preserve the ethical commitments

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

Second Part: By unlimited love and compassion

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

Third Part: By the depth of discernment

Turning Afflictions into Practice

Excerpt From: Shamar Rinpoche. “Boundless Wisdom: A Mahāmudrā Practice Manual.”

Although it is said that there are 84,000 afflictions, in fact they are beyond enumeration. Broadly speaking, they can be generalized into five groups: attachment, anger, ignorance, jealousy, and pride.

When you turn them into practice by recognizing their true nature, all 84,000 afflictions are resolved in an instant. At that moment, Buddha nature reveals itself spontaneously in the five forms of wisdom. That is the far-reaching result of turning afflictions into meditation. The fundamental nature of mind is pure wisdom. In other words, the five forms of wisdom are the innate nature of mind, commonly known as Buddha nature. When the mind is obscured by ignorance, these pure qualities are distorted, and they appear in us as the five forms of affliction. In reality, they are the five forms of wisdom. Thus, the true nature of all afflictions is in no way different from the true nature of mind. If we can only see that the mind and all its afflictions are intrinsically empty and unborn, ignorance will be eradicated in an instant.

Afflictions are sometimes known as poisons, while wisdom is described as nectar. For this reason, the instruction on turning afflictions into meditation is called the instruction on transforming poison into nectar.

The first of the afflictions is attachment. When the intrinsic nature of attachment is recognized as empty “and unborn, it reveals itself as discerning wisdom. In discerning wisdom, all things are perceived distinctly, as they truly are. This is as much as one can say about a Buddha’s wisdom, that a Buddha intuitively knows how and why things are the way they are. It is said that when a Buddha looks at the tail of a peacock, he can instantaneously tell what karmic causes and conditions have brought about all the different colors in each feather.

The second affliction is anger. When the true nature of anger is recognized, anger reveals itself as the wisdom of the expanse, dharmadhātu wisdom. This is when every experience is recognized as inseparable from emptiness, mind’s true nature. In the emptiness of mind, every experience is an experience of spaciousness. In the emptiness of mind, every arising phenomenon occurs within the all-encompassing expanse and liberating quality of awakening.

The third affliction is ignorance. When the innate nature of ignorance is recognized as empty and unborn, it reveals itself as mirror-like wisdom, sometimes known as all-knowing wisdom. There are no limits to knowledge in omniscience, neither “In enlightenment, pride is transformed into the wisdom of nondiscrimination, also called the wisdom of equality. You realize that in the emptiness of mind, all things are undifferentiated in that they are equally empty.”

The fourth affliction is pride, or ego clinging. It is the discrimination between self and others. In any given situation, we generally favor ourselves over others. In enlightenment, pride is transformed into the wisdom of nondiscrimination, also called the wisdom of equality. You realize that in the emptiness of mind, all things are undifferentiated in that they are equally empty.

The fifth affliction is jealousy. In enlightenment, jealousy is transformed into task-accomplishing wisdom, the wisdom of activity. A Buddha, knowing the wishes, capacities, and abilities of all sentient beings, is best able to help them. Here, the term Buddha is used in the broadest sense, and is not confined to a specific historical Buddha.

The afflictions are like poisons for as long as they are not transformed into wisdom. The technique for turning the afflictions into practice is exactly the same as for turning thoughts into practice.

First of all, be aware of the arising of an affliction and identify it; look at its nature. Then relinquish all attachment to the feeling. Finally, do not be apprehensive or hopeful regarding the outcome, but accept any eventuality with courage and confidence.

Be like a lion in the face of hardship and difficulties. Be as free from attachments as the wind blowing through the sky. Be like a madman, without false pretenses and artificiality. The same technique is applicable for all afflictions.

Among the five afflictions, some are easier to detect and identify. Anger, for instance, is usually easy to see. Jealousy and attachment are also not well hidden. However, when you are beset by pride and ignorance, you do not usually know they are there. To be self-centered in our thinking is such an ingrained habitual tendency that it takes both time and patience to eradicate it. When you are ignorant, you are not always intelligent enough to know it. However, once you have dealt with the more apparent afflictions, you will also be able to deal with the more hidden ones in the course of practice.

Sometimes a very advanced meditator has a great deal of difficulty in finding ways and means to further his or her practice and realization. So, after successfully turning the afflictions into meditation by recognizing their true nature, an advanced meditator may go further by deliberately generating even stronger afflictions in order to give impetus to his or her practice. In so doing, the meditator takes the practice to a higher level of realization. People may be understandably outraged by this person’s obnoxious behavior. The reason is that there is no way they can tell that a meditator with pure motivation is practicing the transformation of afflictions into higher realizations.

Marpa was a good example of a practitioner engaging in this kind of practice. Apart from being a great teacher and translator, Marpa was a landowner. People who had practical dealings with him considered him to be a very disagreeable person, proud and aggressive, with insatiable greed. However, the great scholar and mahasiddha Naropa once said to him:

“Other people see you as having very strong afflictions. However, in your mind, an affliction is like a snake twisted into a knot. It straightens itself out in less time than it took to tie itself into the knot.”

Some lamas in Tibet were known to behave like Marpa in the hopes of misleading people into thinking that they were on the exalted level where strong negativity of mind was fuel to their practice. They indulged themselves wantonly in loose living.

But without Marpa’s realization, their behavior was only harmful. It did not help their practice and certainly should not have been seen as an indication of high realization. They might have behaved like Marpa, but they were not highly realized like him.

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

2022 #4 Mentoring on the Spiritual Path

Mentoring on the Spiritual Path

What is the place of tradition and spiritual friends in our current world?

One day, Ananda and the Buddha were sitting alone on a hill together, overlooking the plains of the Ganges. Having served as the Buddha’s attendant for many years, Ananda often shared his reflections and insights with him. This afternoon, Ananda spoke. “Dear Respected Teacher,” Ananda said. “It seems to me that half of the spiritual life is good friendship, good companionship, good comradeship.” But the Buddha quickly corrected him: “Not so, Ananda! Not so, Ananda!” He continued, “This is the entire spiritual life, Ananda, that is, good friendship, good companionship, good comradeship. When a monk has a good friend, a good companion, a good comrade, it is to be expected that he will develop and cultivate the noble eightfold path.” The Buddha skillfully removed Ananda’s idea that the sangha and the dharma are separate. One is not half of the other; the sangha is not merely helpful in realizing the path. The sangha is the path. Spiritual friendship is the path.

Kalyana Mitra

In Sanskrit, Kalyana Mitra means “spiritual friend.” Kalyana may be translated as “good, true, virtuous, upright, or beneficial,” and Mitra is the root word for maitri, which means kindness. A Kalyana Mitra is someone who helps you to realize your deeper aspirations, one who uplifts your path to a higher level of ethical and spiritual well being with a selfless kindness.

Many people, presented with so many teachings praising the practice of meditation and solitude, think Buddhism is a practice for loners. But the Buddha’s encouragements to practice in solitude were balanced with an ardent emphasis on cultivating worthy friendships. Throughout his teaching career, the Buddha spoke again and again about the pivotal importance of Kalyana Mitras in order to succeed in one’s practice, stating that there is no other factor so conducive to the arising of the noble eightfold path as good friendship. “Just as the dawn is the forerunner of the sunrise, so good friendship is the forerunner for the arising of the noble eightfold path,” the Buddha stated. The “Discourse on Happiness,” which extols thirty-two blessings of a happy life, begins with “To avoid foolish persons and to live in the company of wise people… this is the greatest happiness.”

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

#5.Find liberation through both reflection and analysis.

Our minds have two related abilities: to look at things in general and to examine details. In Tibetan these are called tokpa and chöpa. The first is like identifying a forest; the second is like examining the trees in that forest. We should apply these faculties to understand our disturbing emotions.

For example, if you notice that you feel upset, you can ask: Why do I feel upset? Because I have been insulted. What was said that made me feel so insulted? Why did that insult me, when it didn’t insult my friend? Examine the situation from all angles: from your point of view, from the other’s point of view, from the dharmic view, from the worldly view, in relation to the past, present, and future. Learn everything there is to know about the subject and get to the bottom of it.

Once the light of your critical intelligence fully shines, it will be easy to free yourself by applying the Lojong practices such as tonglen. It’s important to do this practice systematically, going from general to specific, without skipping around. If you jump from one general theme to another, or from one detail to another, then you won’t learn much. You will be dwelling in vagueness. This process requires effort and may take you out of your comfort zone. But it is a process you can master, whether you’re an intellectual or an artist, whether you’re educated or uneducated. It’s a matter of using your innate emotional intelligence to understand your own experience. Learning how to apply these two mental faculties will make you feel confident and self-reliant. You will be able to understand the mind deeply from your own experience. In this way you will become a great teacher to yourself as well as a benefit to others.

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

#6. Dharma Roadside Dialogue 2022. Czech & Slovak Fellowship Dialogue.Meditation advice.

How to reflect on the qualities of the Three Jewels?

#7. Dharma Roadside Dialogue 2022. Prayers & Mantra

The importance and benefits of mantra recitation.

The importance of prayer (without falling into a dualistic or theistic mode).

How to develop confidence in the reality of the presence and help of the deities.

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

#8. Dharma Roadside Dialogue 2022. Confidence and control.

#1 Exposé

#2. Dialogue.

#9.Dharma Roadside Dialogue 2022. Renunciation.

#1 Exposé

#2 Dialogue

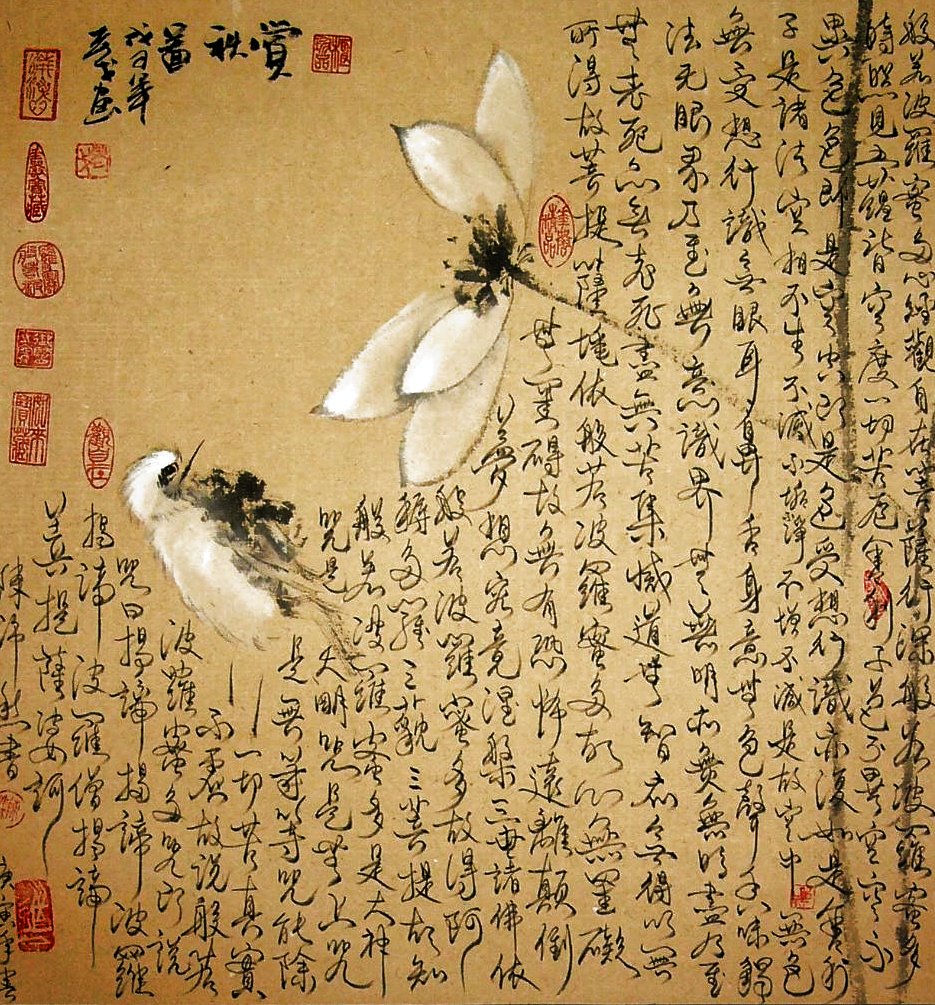

The Sutra of the Heart of Transcendent Knowledge

THE SUTRA OF THE HEART OF TRANSCENDENT KNOWLEDGE

Thus have I heard.

Once the Blessed One was dwelling in Rajagriha at Vulture Peak mountain, together with a great gathering of the sangha of monks and a great gathering of the sangha of bodhisattvas.

At that time the Blessed One entered the samadhi that expresses the dharma called “profound illumination,” and at the same time noble Avalokiteshvara,the bodhisattva mahasattva, while practicing the profound prajñaparamita, saw in this way: he saw the five skandhas to be empty of nature.

Then, through the power of the Buddha, venerable Shariputra said to noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, “How should a son or daughter of noble family train,who wishes to practice the profound prajñaparamita?”

Addressed in this way, noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, said to venerable Shariputra, “O Shariputra, a son or daughter of noble family who wishes to practice the profound prajñaparamita should see in this way: seeing the five skandhas tobe empty of nature.

Form is emptiness; emptiness also is form. Emptiness is no other than form; form is no other than emptiness. In the same way, feeling, perception, formation, and consciousness are emptiness. Thus, Shariputra, all dharmas are emptiness. There are no characteristics. There is no birth and no cessation. There is no impurity and no purity. There is no decrease and no increase. Therefore, Shariputra, in emptiness, there is no form, no feeling, no perception, no formation, no consciousness; no eye, no ear, no nose, no tongue, no body, no mind; no appearance, no sound, no smell, no taste, no touch, no dharmas; no eye dhatu up to no mind dhatu, no dhatu of dharmas, no mind consciousness dhatu; no ignorance, no end of ignorance up to no old age and death, no end of old age and death; no suffering, no origin of suffering, no cessation of suffering, no path, no wisdom, no attainment, and no nonattainment.

Therefore, Shariputra, since the bodhisattvas have no attainment, they abide by means of prajñaparamita. Since there is no obscuration of mind, there is no fear. They transcend falsity and attain complete nirvana. All the buddhas of the three times, by means of prajñaparamita, fully awaken to unsurpassable, true, complete enlightenment.

Therefore, the great mantra of prajñaparamita, the mantra of great insight, the unsurpassed mantra, the unequaled mantra, the mantra that calms all suffering, should be known as truth, since there is no deception.

The prajñaparamita mantra is said in this way:

OM GATE GATE PARAGATE PARASAMGATE BODHI SVAHA

Thus, Shariputra, the bodhisattva mahasattva should train in the profound prajñaparamita.”

Then the Blessed One arose from that samadhi and praised noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, saying, “Good, good, O son of noble family; thus it is, O son of noble family, thus it is. One should practice the profound prajñaparamita just as you have taught and all the tathagatas will rejoice.”

When the Blessed One had said this, venerable Shariputra and noble Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva mahasattva, that whole assembly and the world with its gods, humans, asuras, and gandharvas rejoiced and praised the words of the Blessed One.

Lotsawa bhikshu Rinchen De translated this text into Tibetan with the Indian pandita Vimalamitra.It was edited by the great editor-lotsawas Gelo, Namkha, and others. This Tibetan text was copied from the fresco in Gegye Chemaling at the glorious Samye vihara. It has been translated into English by the Nalanda Translation Committee, with reference to several Sanskrit editions.© 1975, 1980 by the Nalanda Translation Committee. All rights reserved

Saga Dawa Heart Sutra Recitation, 4 – 5 June 2020, Global from Khyentse Foundation on Vimeo.

Pratique de Tchènrézi

Explication de la Pratique de Tchenrezi.

Tchenrezi est la personnification de l’amour et de la compassion éveillés des Bouddhas. Cette méditation simple et très profonde s’appuie sur la récitation d’un mantra combinée aux techniques de visualisation du Vajrayana. C’est un moyen très habile pour purifier tous les obscurcissements de l’esprit. La récitation de son mantra “Om Mani Pémé Houng” amène d’immenses bienfaits pour soi-même et autrui. Il a le pouvoir de libérer tous les êtres de l’existence conditionnée.

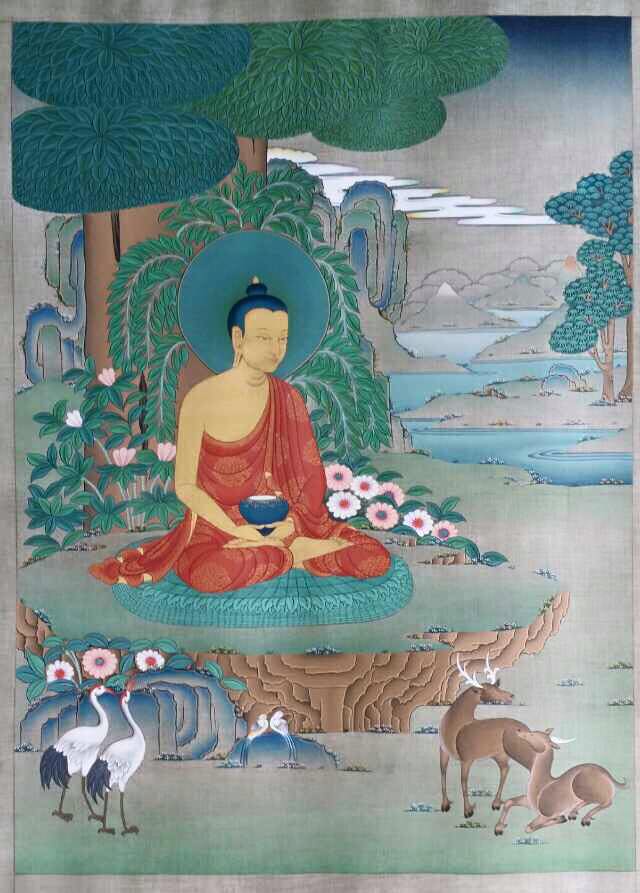

The Path of the Sugatas

A concise practice of Buddha Shakyamuni with offerings

Composed in Tibetan and translated by Kunzig Shamar Rinpoche

For whoever would be a sensible follower of the Buddha, there is no other way to receive his blessing than actual practice with undivided devotion. Therefore this concise sadhana of Buddha Shakyamuni has been composed.

The Benefits of this Practice

The most excellent individual will be able to actually see the Buddha and listen directly to the profound Dharma teachings. He will quickly attain the state of Buddha-hood. The benefits for ordinary people are that in all future lifetimes, they will be born in whatever place the Buddhas are dwelling and become disciples. Because of constantly receiving blessings, their minds will be happy; negative forces will have no effect; and the bad obscurations of karma will be purified. The intellect will be sharpened and awareness increased, and love and compassion will arise. They will have the ability to greatly benefit sentient beings. There are many more benefits of this practice, limitless in number.

Seeing that the one great need at this time is to supplicate directly the Buddha, Guide of the World, I compiled and translated this text in order to clear up the evils of this troubled time, and in order to increase the good fortune and merit of beings.